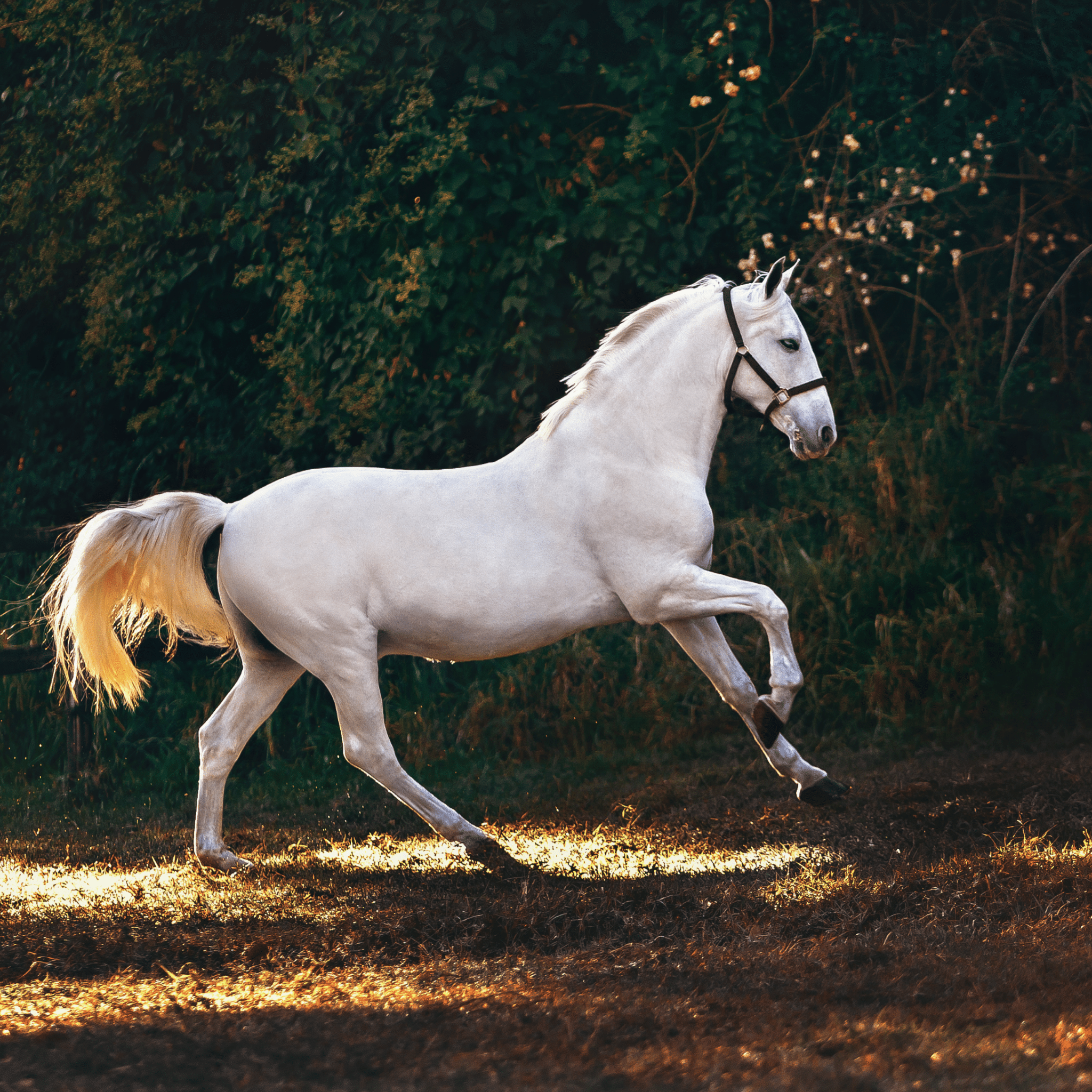

Self-carriage is a vital part of achieving true collection. It is the ability of the horse to maintain its frame, rhythm, speed, and balance without the rider having to micromanage everything.

In my last article on Correction vs Preemption, we discussed how there is a difference between correcting a mistake and preempting a mistake. Before you continue, I highly encourage you to read the Correction vs Preemption article to get the basics of the concepts we will discuss here as this article is a continuation of the same discussion.

The Difference Between Preemption and Correction

In developing self-carriage, we instinctively want to prevent the horse from stepping out of line. However, as we learned in the previous article, this thinking is actually quite backward. In order to learn, the horse must be allowed to make mistakes. Having those mistakes corrected will teach the horse not to make that mistake again and prevent the formation of bad habits.

For example, if you feel the horse’s shoulder dropping and you block the shoulder from dropping, that is preemption, not correction. The shoulder hasn’t been allowed to drop, but the horse hasn’t actually learned not to drop his shoulder. In order for the horse to learn not to drop his shoulder, he has to actually follow through with dropping his shoulder. Then, you correct him and he learns from that correction. Propping up the shoulder acts as a crutch. The moment you take that crutch away, his shoulder drops. Rather than forming the good habit of holding his shoulder up where it should be, he has formed a bad habit of dropping his shoulder the moment you take his crutch away. The horse becomes dependent on you to micromanage every move he makes and the moment you stop micromanaging he falls apart. This is how you destroy a horse’s ability for self-carriage.

Encouraging Proper Self-Carriage

The key to self-carriage is “self.” The horse has to be responsible for its own body. If you are constantly propping them up, you are carrying them as opposed to them carrying themselves. They must learn the self-control necessary to obtain self-carriage. So, how do you develop this self-control and encourage proper self-carriage? The answer is one you’ve probably heard before; make the right thing easy and the wrong thing difficult.

Make the Right Thing Easy and the Wrong Thing Difficult

You cannot force a half ton animal to do anything. Instead, you have to find a way to encourage the behavior that you want. In this case, we are focusing on proper self-carriage which includes maintaining frame, rhythm, speed, and balance without rider intervention. We can encourage all of these things by making the right thing easy and the wrong thing difficult.

Now, keep in mind that this principle is often misunderstood. Making the wrong thing difficult does not mean we are punishing the horse for doing the wrong thing. It simply means we are presenting the horse with two choices. One choice is going to be less work than the other. The choice that is easiest will be the correct choice that we want the horse to choose. However, it remains the horse’s decision. If the horse really wants to choose the hard way, let them. Horses are inherently lazy creatures. They won’t keep choosing the harder option forever. Let’s look at an example to better understand how this works.

Example of Training for Self-Carriage: Correcting a Horse that Drops Their Shoulder

If you have a horse that drops its shoulder, constantly picking up the shoulder isn’t the most efficient way to correct them. If you simply cue them to pick their shoulder up as soon as they drop it, they may slowly start dropping their shoulder a little less, but they won’t have any real motivation not to drop the shoulder. This is where you need to make the right thing easy and the wrong thing difficult.

Prerequisites

So, let’s establish the ground rules. The right thing is not to drop the shoulder. The wrong thing is dropping the shoulder. In order to proceed, your horse needs to know some sort of lateral movement. I prefer to use the shoulder-in for this type of correction. However, you can make it work with a simple leg yield if your horse doesn’t know how to do a good shoulder-in. Keep in mind, whichever lateral movement you choose, your horse should be able to do it very well before trying this. The lateral movement is simply being used as a tool to fix a separate issue. This is not the time to be training a shoulder-in or a leg yield as you should only be addressing one thing at a time. For the sake of this example, I will be using the shoulder-in to correct the dropped shoulder. However, remember that it can be substituted with a leg yield or any other lateral movement of your choice.

Training Exercise

Setup: You start the exercise by simply riding as you normally do, doing whatever exercises you had originally planned to work on that day. Never anticipate the horse dropping his shoulder, but remain prepared for it.

Step 1: When the horse does drop his shoulder, abandon whatever other training you were working on before the shoulder dropped and transition straight into a shoulder-in.

It is physically impossible for a horse to perform a proper shoulder-in without picking his shoulder up. Now, when you try to transition into a shoulder-in with a dropped shoulder, your horse will get a bit stuck. He will need a few moments to rearrange himself to do a proper shoulder-in. Don’t get frustrated or angry. Don’t up the pressure. Continue gently asking for the shoulder-in until he rearranges himself and gives it to you. This is why it is important for him to know the shoulder-in movement well. He needs to know exactly how to rearrange himself to perform the movement properly in order for this to work.

Step 2: Once the horse gives you a few nice strides of shoulder-in, transition out of the shoulder-in and resume whatever exercise you were doing right before he dropped his shoulder.

The key is to act like nothing happened. If he drops his shoulder again, immediately ask for another shoulder-in. Rinse and repeat until he figures out that the shoulder-in really isn’t that fun and maybe he should just keep that shoulder up where it belongs. It usually doesn’t take long for the horse to find the correct answer. The shoulder-in should be used in other contexts as well so the horse doesn’t just view the shoulder-in as a punishment that is only applied when he drops his shoulder.

The Importance of Choice in Self-Carriage

In the previous example, the shoulder-in is being used as a correction, not a punishment. Properly applied correction easily encourages the horse to find the right answer on its own. The horse comes to the point where they are always prepared to move into a shoulder-in (or another lateral movement of your choosing). This is, after all, the point of self-carriage. A horse with good self-carriage is ready to move into a shoulder-in or other lateral movement at a moment’s notice. There should be no hesitation. Rather, it should be one fluid transition into and out of the movement. This is a fundamental part of collection.

How Do I Know If My Horse Has Good Self-Carriage?

A horse that chooses self-carriage will be far more fluid in its movements and transitions than one that is being forced into a frame. A good test to know whether or not your horse is achieving self-carriage is to loosen your reins. If you loosen your reins to the point where you no longer have contact with your horse’s mouth and your horse falls apart, he doesn’t have proper self-carriage. However, if you loosen your reins and your horse keeps itself together, then it’s safe to say that you are probably on your way to achieving proper self-carriage. A horse must choose to maintain self-carriage. True self-carriage can’t be forced.